Reflecting on MONUMENTS

DECEMBER, 2016

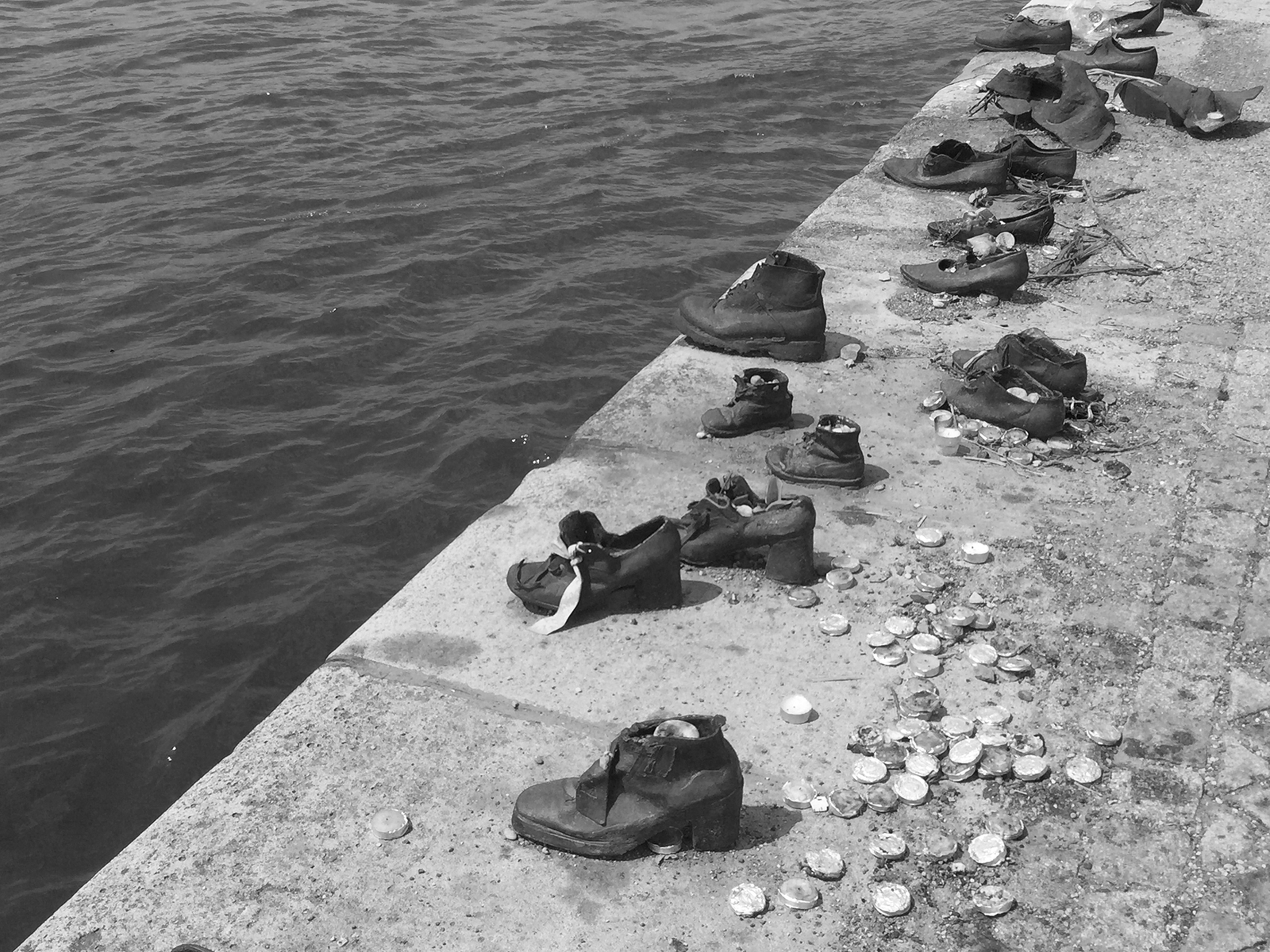

Photo by Gundula Friese

While statues bring beauty, inspiration or provocation; the job of a monument is to help us remember.

Monuments pay tribute to a person or event that is deemed significant to our collective history.

On an evening in November on the way back from a lecture about identity and community, photographer Gundula and I ran across an art installation of upturned buses placed in front of Brandenburg Gate called “Monument.” A different kind of monument.

Growing up in Wisconsin and spending many years in San Francisco, I didn’t encounter many monuments.

Now living in Berlin, I’m saddened by how many monuents represent some facet of war.

Traveling on the Danube with my mom last spring we witnessed many monuments and memorials. Each celebrating victory and or honoring loss. Two sides of the same coin.

Bratslava, Slovakia, King Svatopluk 870-894, greatly expanded Moravia in the area of Slovakia

Vienna, Austria, Maria Theresa, ruler of Habsberg Empire 1740-1780

Photographs by Laura J. Lukitsch

Budapest, Hungary, Hero’s Square, built in 1896 to mark 1000 years of Hungary

Budapest, Hungary, “Shoes on the Danube” honoring those shot here during WWII.

In my neighborhood, and in fact around Berlin and other cities in Europe, there is another kind of monument, the stolpersteine, or stumbling block. Created by artist Gunter Demnig it is a way of remembering those exterminated by the Nazi regime. A small bronze monument is placed on the sidewalk outside the last known residence of someone killed by the Nazis.

It is a way of remembering those that lost their lives, but also to be confronted with the reality of how easy it is for fear to lead humans to do terrible things to people they consider to be ‘the other.’

I think it is important for future generations to remember the atrocities we have committed. These acts impact generations of survivors.

Confronted by the evidence of WWI, WWII and the end of the cold war, it somehow felt that we should have learned that war does not solve our problems. Yet wars continue to kill and displace people; and to create heroes and victims.

Somehow history feels more alive with these remembrances. The young Germans I meet seem to embrace the fundamental principle of the post WWII constitution that reads “Human dignity shall be inviolable.”

NATIONAL MEMORIAL

FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE

Montgomery, Alabama

After coming to Berlin and seeing all of the monuments that acknowledge the wrongs done in the past, I was struck thinking that in the US, there have been no place where people can go to acknowledge and honor those who died from the lynchings that took place from the 1800s up to the time of the civil rights movement, and even beyond.

While confederate monuments dot the south, there had been nothing to remember those black citizens lost their lives so unjustly after the civil war ended.

Then I learned of the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice planned to open in 2018 that will recognize the 4,384 documented victims of lynchings.

You can read more about the monument from this Atlantic article. This is a step in the right direction. Acknowledgement of wrongs is one of the most important parts of the healing process when people have been wronged.

In in many cities in Europe, statues and monuments that no longer represent the ideas and ideals of the current population are often removed and themselves removed and living for some time either in a lapidarian or buried underground.

Berlin has unearthed some of these and included them in a permanent exhibit called Unveiled. This seems like an option for many public confederate monuments in the US south.

Mouments

#ParkProjectBerlin

The buses are a different kind of monument, created by Syrian-German artist Manaf Halbouni. He was inspired by a Reuters photo taken in Aleppo, of standing buses blocking an intersection used as cover from snipers in 2016.

To me, the monument stands for survival and the will to survive. It is a collective vision of courage.