Public Figures

11 THINGS I LEARNED SPENDING A YEAR IN BERLIN’S PARKS | part 3

As I spent time in Berlin’s parks I started to understand the story of Berlin through its statues.

In the 1800s, statues glorify national identity, featuring enlightenment artists and thinkers. After the Napoleonic wars, larger than life monuments celebrate victory. And after the Second World War, monuments remember those who were victims of war.

Statues are a form of PR. And the messages being broadcast change over time with who is doing the broadcasting and what message they want to convey.

Today, new figures are starting to emerge. And existing figures are starting to be re-examined.

Fallen Heroes

The events surrounding the violence and demise of the DDR (East Germany) are well documented throughout Berlin. Signs stand at various historical spots to inform visitors of events, escapes, important details and significant moments.

I’m interested in the history we don’t see.

Look close and outside of central tourist areas, you’ll find that in former East Berlin there are very few Prussian statues or monuments. Many were removed by the West before the split. Some statues were buried for safekeeping. Some were removed by Hitler before the war while he was making space to build the foundation for Germania.

Statues have had a habit of moving depending on who was in power, as you can see illustrated in the video Tiergarten: Moving Monuments.

Creating Heroes

Heroes are created, usually by the winners. But as history shows, power shifts tend to change our view of who is a hero, and why.

Often, former heroes have no public context: from the money counter in Mitte to the founder of the sports movement in Hasenheide Park. Bismarck’s moment in the heart of the city references colonial powers and the subjugation of Africa, also without explanation.

I went on a few monument scavenger hunts during my year.

One hunt was inspired by an installation project for PremArts and Berlin Gallery Weekend. The theme was bergs, or mountains of Berlin. So I went in search of Trümmerfrauen, rubble women, who have been credited with removing the broken bricks of Berlin after the bombings of the Second World War. Those bricks formed Trümmerbergs, or rubble mountains.

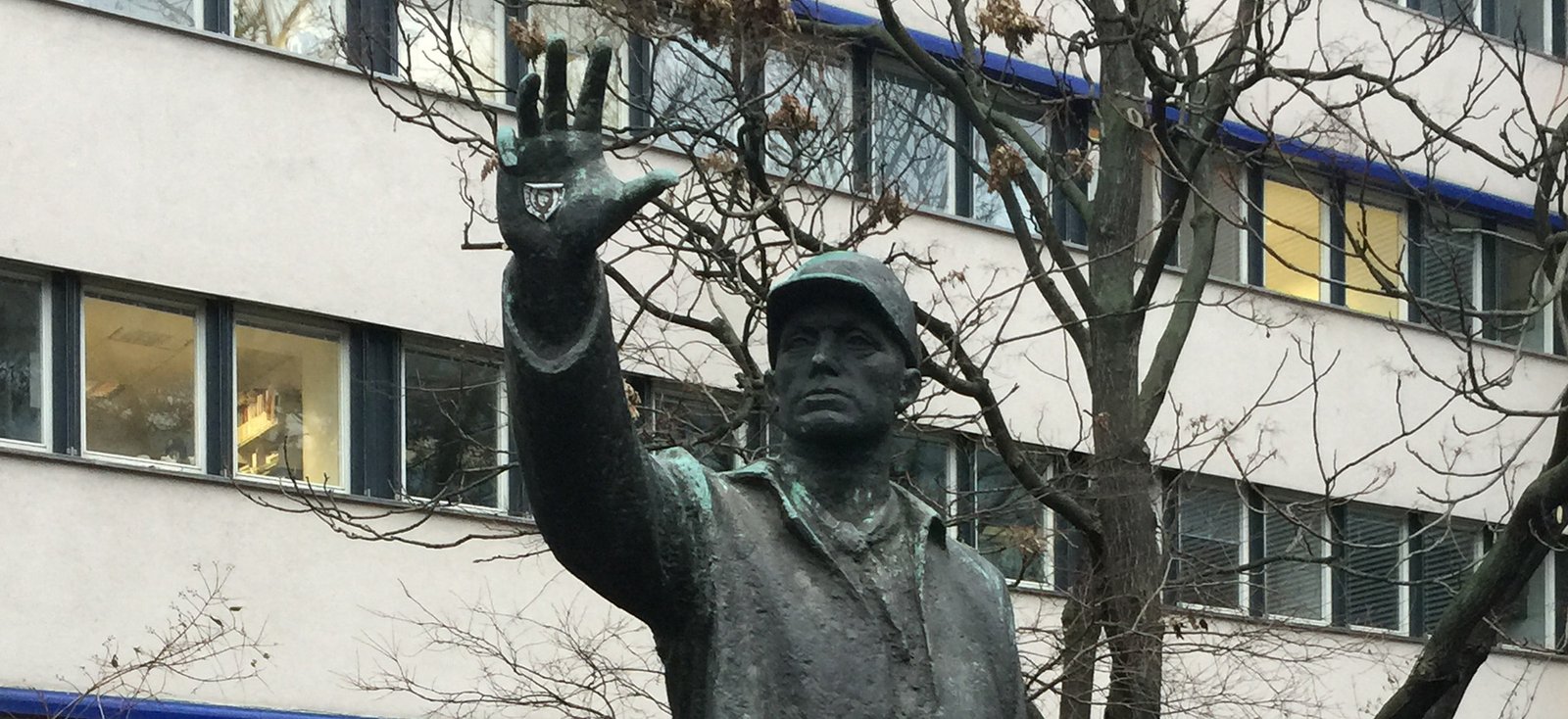

Trümmerfrauen are memorialized in statues throughout both former eastern and western Berlin. I found three of five documented statues.

They are mentioned in museums and history books as post-war heroes. Yet new historical data offers a different view. Rather than heroes, it shows that most of the women were enlisted for the task, mostly for economic reasons.

History books and US government footage have created a new reality.

I think it is interesting that the statue in Volkspark Hasenheide is rather docile. The rubble woman sits with the anvil resting on her dress. She looks tired. Her back is to the entrance and she is tucked away in a patch of bushes, almost out of sight, mostly forgotten.

—

In my hunts, I looked for but found no statues acknowledging the Turkish workers who also contributed to the second wave of the rebuilding of Berlin. It is not surprising as that is such recent history but I looked anyway.

While I couldn’t find any statue in Berlin I did discover there had been a Workers Monument honoring the over 865,000 Turkish workers who went to Germany between 1961-1973. It was erected in Instanbul during the 1970s when the city had decided to add civic statues to the public sphere. The statue, which stood outside of the Public Labor Employment Office in Tophane (where Germany recruited workers) was quickly vandalized. You can read more about the history of this statue in a great article on the Red Thread.

Three Women

Berlin’s official protected monuments include 72 men of historical importance, but only three women. The list of people recognized by the city of Berlin, based on 2004 data, includes just over 7,000-people. Fewer than 300 of these are women.

The balance reflects history. Yet, that lack of ‘real women’ in our public spaces impacts our view of women today. In 2017 I visited Vienna, Austria, and Bern, Switzerland. Both cities have prominent statues of powerful women in the center of these cities. Yes, one was a queen and one an allegory, but as an American, it was the first time I saw a statue of a powerful woman in such a prominent public space, and it made a deep impression on me.

The three official monuments dedicated to recognized women of Berlin include Queen Luise of Prussia whose statue is in Tiergarten; artist Käthe Kollwitz whose friend and fellow artist created a statue of her which now can be found at Kollwitz Platz in Prenzlauer Berg; and artist Hannah Höch, the founder of Dadaism (although her monument does not depict her, but rather a Dadaist work of hers).

I am aware of eight statues of women figures in total. Only eight.

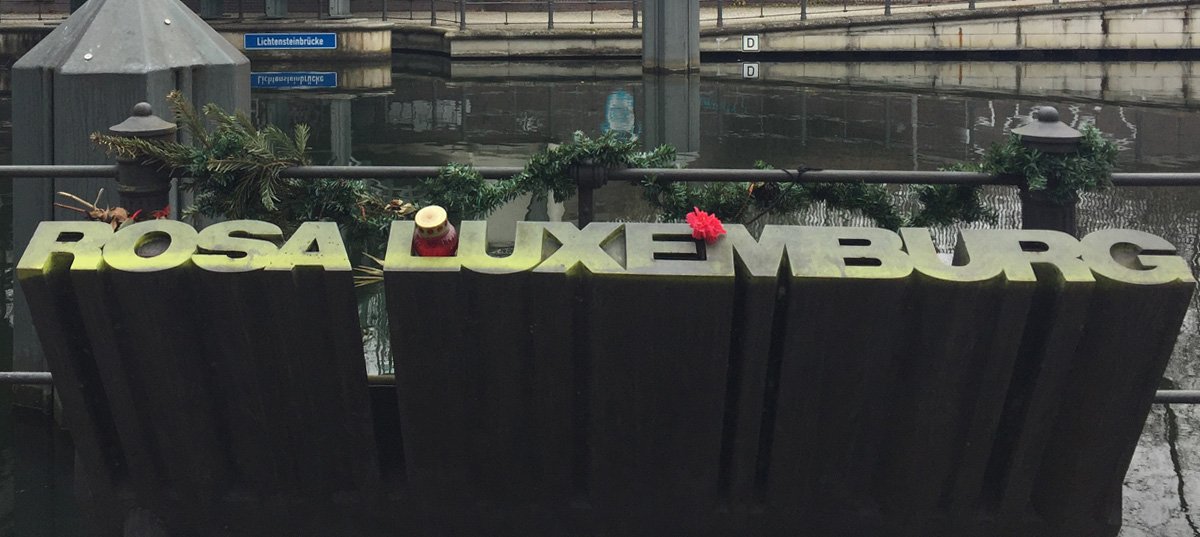

The other five include politician Clara Zetkin; activist and thinker Rosa Luxemburg; politician Mathilde Jacob; Queen Sophie Charlotte; and Austrian nuclear physicist Lise Meitner, new to the group as her statue joined the row of male academics greeting visitors to Humboldt University in 2014.

This imbalance is common throughout the world. Many cities are stepping up and finding ways to correct the disparity. Berlin has started with street names. They require a balance between men and women when naming streets.

In April 2018, London unveiled the first woman statue in Parliament Square, suffragist Millicent Fawcett.

In June 2018, New York City launched She Built NYC, an advisory panel to commission local artwork honoring women their contribution to the history of NYC. They plan to create five monuments by the end of 2018.

New Faces

I envision cities like Berlin moving towards the portrayal of new faces and new narratives in their public spaces.

As this happens, I wonder what new virtues we can venerate. Is there a way beyond the dichotomy of war and peace?

Maybe monuments will take different forms.

The French artist JR is placing faces of everyday people in public. Cities are now using mobile technology and QR codes to tell different stories. And technology companies are offering platforms for geotagged mobile storytelling.

Just this summer a new monument of six colorful calla lilies was dedicated to the homosexual emancipation movement.

I think it is interesting to think about who you would honor if you had the chance. What stories would you want to be remembered?